I was 24 years old and had just swapped out my textbooks for a sleek M16 rifle in the U.S. Army. I dropped out of college in hopes of finding financial stability and a promising future defending my country. But about six short months later, after completing basic training and Advanced Individual Training (AIT), I found myself in the heart of Iraq in complete shock. I had just learned how to throw a grenade, shoot a gun, manhandle a machine gun and use a compass. I could not for the life of me understand why I was going so soon.

While I was in Iraq, I kept wondering how it would be when I returned to the States. Would I come back with any missing limbs? Would I return with PTSD? Would I die?

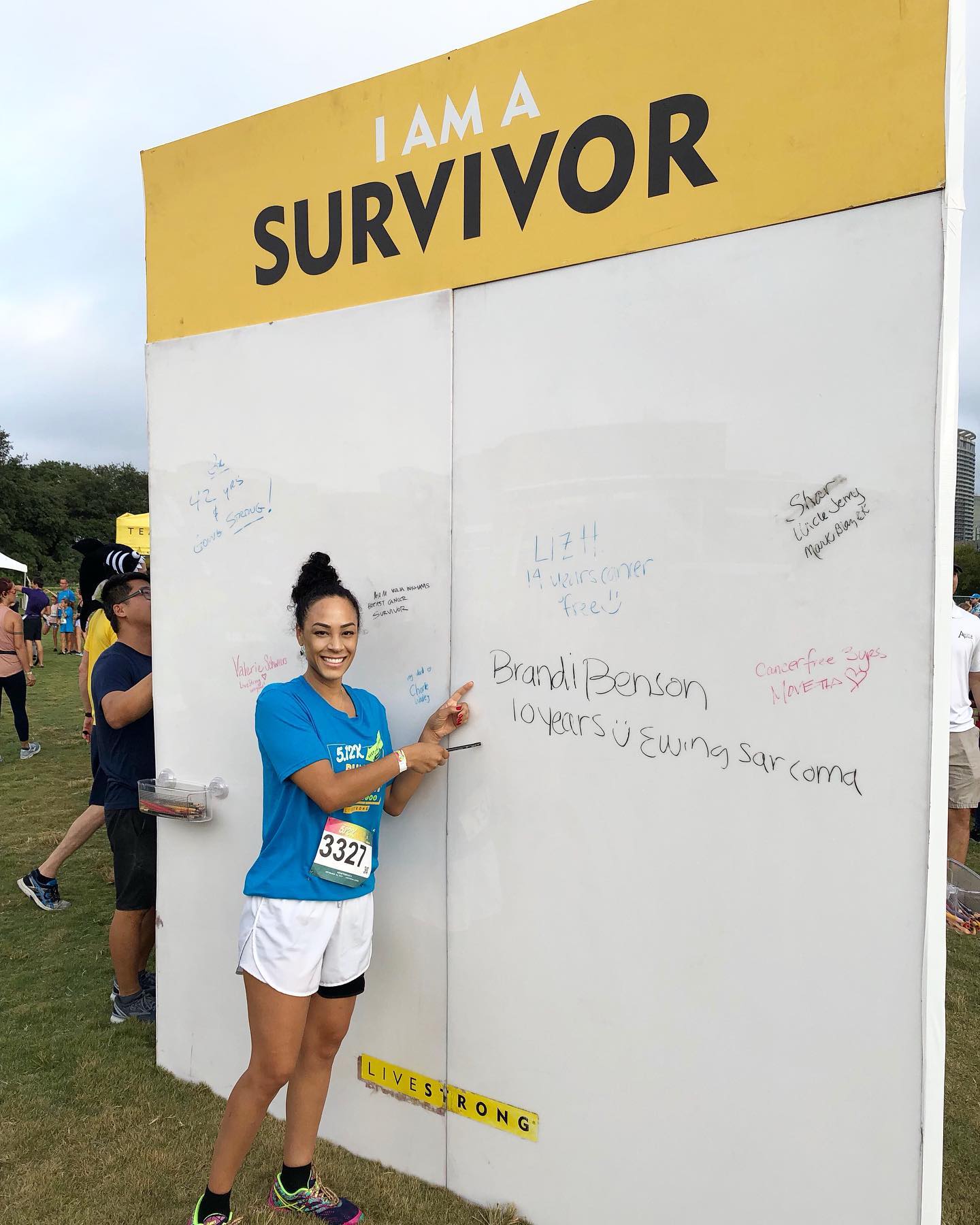

The one thing I did not imagine was returning to my homeland with an enemy inside me—Ewing Sarcoma cancer. As soldiers, we didn’t learn how to prepare for an illness or an attack from within our own bodies. Instead, we learned how to pack bullet wounds, how to clear a room, how to administer an IV and how to tell if a lung had collapsed.

I remember the day my life changed forever like it was yesterday. Doctors surrounded my bed, hesitant to deliver the plan to me.

A doctor shuffled the notes in his hand like a nervous college student reluctant to turn in their test. “Brandi,” he began. “We may have to cut your leg off … but we will try to do everything we can… to save it.”

Ewing Sarcoma is a very rare and aggressive cancer. Only about 200 children and young adults are diagnosed with it every year, and the 5-year survival rate drops the older you are when diagnosed. My team of doctors had never seen such a case and only read about it in textbooks in medical school.

“This cancer is very aggressive,” the doctor continued. “If we do not catch it early, it can spread to your lungs, brainstem and spinal cord. We won’t know until we are in your leg and testing the margins. We cannot promise you.”

The cancer was very high in my leg. It latched onto my adductor muscle in my hip and my groin as if it had a death grip—slowly devouring everything in its path.

I begged and pleaded with the doctors before my 13-hour surgery to save my leg. I was not sure if I would have both of my legs when I woke up or just one. It was pure torture, but the operation had to be done.

After spending more than half of the day on an operating table with my left leg sliced open, I woke up with both of my legs and a new me. But the new me was flawed. Traumatized. Insecure. Scared.

It took a while to understand that the old me was gone. I looked different. I felt different. I acted differently.

I remember clearly seeing a dramatic difference when comparing my legs. My right leg was thick, curvy and healthy. My left leg was thin and disfigured. I had a huge scar that marched up my leg, and the surgeon tied my left quad and hamstring together to create a fuller look.

Despite their creative efforts, I could see my left butt cheek from the front. I had a massive chunk of muscle missing, and I felt so ugly and knew that there would be no one that would accept this “new Brandi.” I couldn’t even accept her myself. I thought the hardest part was over because the cancer was gone. But now I had to live with this new me who I hated.

I slowly began to understand the term “outcast” and yearned for acceptance from the world. Was I worthy of love? Would I ever feel self-love again? Would people point and stare at me? Can I handle this new life? Will I become suicidal? Who is going to love me with a 24-inch scar on my body?

I had questions with no answers because I had just begun my journey of survivorship. I could not care less about the scar, but I wanted to be able to look into the mirror and not see my left butt cheek from the front any longer. I decided to get plastic surgery to try and fill out the gap. A tissue expander was put into my leg, and a few months later, there was enough stretched skin to pull over the hole. But it still did not fix the problem.

I needed volume. I needed mass. Pulling the skin over a sunken pit did nothing. I was so discouraged and upset that I was not only disabled but looked disabled.

I ran from myself. I ran from self-love. I hid in the shadows of my past life and didn’t dare explore the new me. I cried myself to sleep for months, and no one knew how distraught I truly was. I had a vision of who I wanted to be, and who I was at the moment did not match.

The woman I envisioned was carefree and lived by no labels. I romanticized the idea of her but had no roadmap on how to birth her. She was unwaveringly unapologetic for who she was. I loved that about her.

As time went on, I started to realize that I needed to make peace with this new me and love her and rebrand myself. I needed to be constructive with how I lived for the future and not destructive by continually living in the past. By denying myself feelings of worthiness, love and acceptance from others because I felt broken, I was adding to the problem.

True self-love is accepting all of you—there is no ugly in you or bad in you; there is just “you.”

I was so lost in the past that I couldn’t heal the present me. It took many years of therapy, exploration and grief to understand that our physical scars are more beautiful than a baby’s laugh. That part of the body was tried, and it won. Those scars are our battle wounds of survival.

My left leg has more character than Prince Charming. My 24-inch scar is the most loveable thing about me. Your insecurities are actually qualities that make you stand out in great ways.

What we go through to get to this point is impressive. We are worthy not only of love but, most of all, self-love. I’ve gained a respect for my body that I never knew existed. I love me and all of my flaws. I am beautiful. I am unwavering in being unapologetically me.

Don’t be ashamed to be different! Remember, celebrities at red carpet events look for months to find those outfits that stand out and pray they don’t run into someone else wearing the same thing. Our disabilities are our red carpet outfits. We look different—and we look damn good that way, too.