The words “burn pit” may sound like a little hole in the ground, but the open air pits used to burn garbage on military bases across Iraq and Afghanistan are of epic proportions, like that biblical lake of fire.

When Veronica Landry came back to base every day from working as an operations specialist/historian for KBR, the company that set up the Marez and Diamondback bases in Mosul, Iraq, she found little black flecks all over her room. “It was soot and ash from the burn pits all over my room. We were exposed to the burn pits every day,” she says.

Those pits burned everything unwanted on the base: styrofoam, plastic water bottles, air conditioners, vehicles, batteries, medical waste and tires. “We always knew it was tire day because you could see the black smoke was so bad,” Landry says. “It was considered a cost avoidance measure to using incinerators.”

The Environmental Protection Agency website notes that burning trash creates dioxins that endanger the environment and human health. These potent organic chemicals accumulate in the body, and over time dioxins can suppress the immune system, disrupt hormones and cause cancer. While burning trash is outlawed across the U.S. because of the toxins it creates, those laws didn’t apply on military bases.

U.S. President-elect Joe Biden believes his son Beau Biden, who died in 2015 at age 46 of brain cancer, became ill after exposure to burn pits. Beau Biden was deployed to the Balad Air Base in Iraq as part of the Delaware Army National Guard in 2008. “Exposure to burn pits, in my view, I can’t prove it yet, he came back with stage IV glioblastoma. Eighteen months he lived, knowing he was going to die,” said Joe Biden in a 2019 speech to the Service Employees International Union.

And Landry believes chemicals she was exposed to while living on base ruined her health and left her with constrictive bronchiolitis, an incurable lung condition that narrows the small airways. Landry and thousands of vets who served T in Southwest Asia and Africa are dealing with respiratory problems, immune disorders and cancers that they believe were caused by toxic exposure during their military service.

But the Veteran Affairs’ (VA) position is that while smoke from toxic burn pits causes temporary eye, skin and lung irritation, “research does not show evidence of long-term health problems from exposure to burn pits.” As of August 2020, more than 212,000 service members have signed up for the VA’s Airborne Hazards and Burn Pit Registry.

But the Veteran Affairs’ (VA) position is that while smoke from toxic burn pits causes temporary eye, skin and lung irritation, “research does not show evidence of long-term health problems from exposure to burn pits.” As of August 2020, more than 212,000 service members have signed up for the VA’s Airborne Hazards and Burn Pit Registry.

Yet the VA has denied 78 percent of burn pit exposure disability claims as of September 2020. An article in Stars and Stripes revealed that of the 12,582 veterans who made claims since 2007, just 2,828 have been granted. Most vets and their families are handling disabling health problems and paying for medical treatment on their own.

Veterans organizations like The TEAM Coalition, TAPS, Hunter Seven Foundation and Burn Pits 360—plus a bipartisan congressional delegation—are pushing for federal legislation called the Presumptive Benefits for War Fighters Exposed to Toxins Act of 2020. It’s modeled after the presumptive illness law for 9/11 first responders who were diagnosed with cancer years later. Comedian and activist Jon Stewart, who spoke out for 9/11 first responders, also supports this bill that would require the VA to take care of veterans who developed a range of lung conditions and cancers.

“The presumptive bill is the way of removing some of those barriers so military members don’t have to act as [their] own lawyer. That’s a lot of burden to put on someone,” says Julie Tomaska, a veteran of Operation Iraqi Freedom and board member of Burn Pits 360.

And in the meantime, activists are sharing health information like the VA training document, which veterans can use to teach their doctors about chemical exposures and how to document claims. They’re also educating both veterans and the public on the many ways toxic exposure has destroyed so many people’s lives.

Darryl “DJ” Reyes, a retired US Army colonel, used to love running—he ran more than 40 marathons before he began serving in the Persian Gulf in 2003. “Today, I cannot run down to the end of my residential street without being out of breath, lightheaded and with chest pains,” he writes in an email. He blames the burn pits he was exposed to during his service in northern Iraq for his ongoing immune and respiratory problems.

“You would have a thin layer of fine soot all over your clothes, your hair, in your ears and nose,” Reyes writes. “While deployed, troops became sick but chalked it up to the ‘Iraq crud’ or ‘Afghan crud.’ We would get antibiotics to help clear up the sickness. Coughing, wheezing and general upper respiratory congestion were common symptoms.” Still, he considers himself lucky: as a 33-year veteran, his health care is covered.

Landry, a former competitive bodybuilder, uses organic eating and holistic approaches to help deal with a raft of health problems, including brain hypoxia, obliterative bronchiolitis and what her doctor suspects is mixed connective tissue disorder, a condition that’s often hereditary. There’s no history in Landry’s family, but the other cause is exposure to silica and polyvinyl chloride, also known as PVC. A commonly used plastic found in plumbing, plastic straws, food wrappings and car engines, PVC is considered one of the most toxic plastics to humans.

Landry won disability payments connected to her work as a civilian in January 2020. But instead of getting compensation based on the degree of her disability as a veteran would, her settlement is based on her income. Landry receives $4 a week. And she had to fight for nearly five years to get it.

Being your own advocate is key: Landry said that her own lung issue wouldn’t have been discovered if she hadn’t had private insurance coverage and persisted until she found a doctor who agreed to perform an open lung biopsy. The invasive test is the only way to diagnose her lung condition that may be written off as asthma or pneumonia. Still, after her close calls and major surgeries, Landry considers herself lucky to be alive.

Many young vets have died from rare cancers after their service. One of those was Amie Muller, a mother of three who did two tours with the Air Force and Minnesota Air National Guard at Balad Air Base. She was diagnosed with stage III pancreatic cancer at age 36 a few years after leaving service. Muller died nine months later. Her husband Brian Muller, Tomaska and other friends now run the Amie Muller Foundation, which gives grants to veterans battling pancreatic cancer.

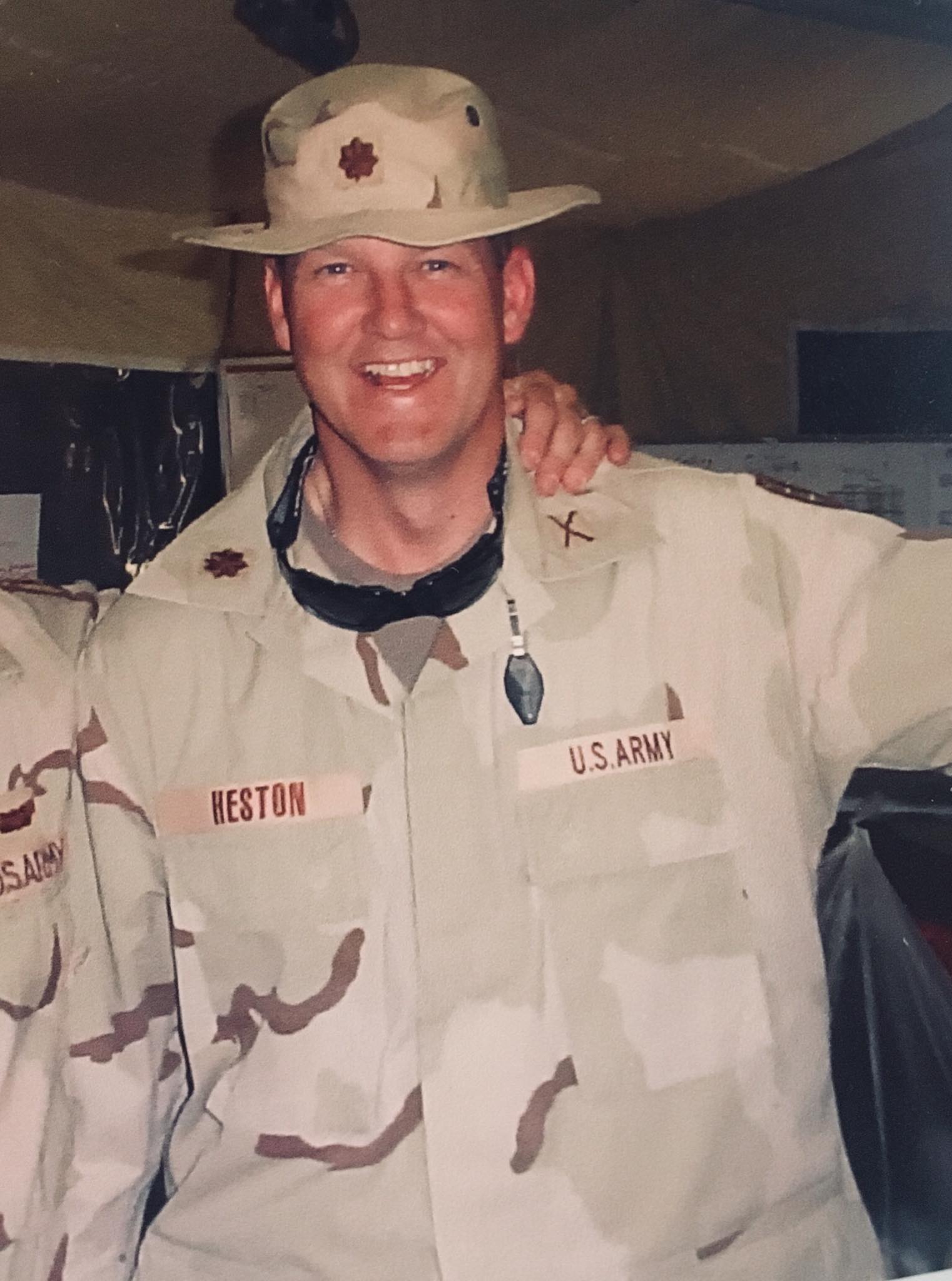

Pancreatic cancer also killed husband Mike Heston, a Brigadier General in the Vermont Army National Guard who served multiple deployments in Afghanistan between 2003 and 2012 over his 34-year military career. In an interview with Radio.com, June Heston said during her husband’s last deployment, ash from burn pits was damaging the aircraft. To protect the equipment, base officials moved the burn pit closer to the barracks where her husband and his troops slept.

General Heston’s last deployment ended in 2012 and he returned to Vermont and took over as second in command of the Vermont National Guard in 2013. June Heston said her husband advised his troops to sign up for the VA burn pit registry when it came out in 2014. “He said you don’t establish a registry unless you know there’s a problem,” she said. Her husband joined the registry, but didn’t think he would need to file a claim.

In 2016, Heston started having severe back pain and fatigue, losing 75 pounds without trying. After 10 months of tests and unclear results, he was diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer in January 2017. He began treatment with Thomas Abrams, M.D., an oncologist at the DanaFarber Cancer Institute. Abrams had never heard of burn pits before he met the Hestons.

“I said to myself, ‘This can’t be good. This has to be contributory to human diseases, certainly lung diseases, and probably cancer,’” recalls Abrams in a phone interview. “Though it’s very hard to pin down a specific cause of any cancer, there certainly would be enough toxins in the smoke to contribute to human cancer.”

Abrams wrote a letter to the VA connecting Heston’s cancer with his service for his disability claim. Heston’s claim was denied by the Department of Defense because claims must be filed within 180 days of “qualified service.” But Heston received VA benefits before he died in November 2018.

Abrams encourages more vets to join the VA burn pit registry so it’s easier to see patterns. “These diseases take years to develop, so exposure itself is not going to show signs of disease until years later,” he says.

The VA is still studying a September 2020 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, which found the agency needs to do a better job of gathering data and evaluating disability claims. A potential 3.7 million people could have been exposed to toxic smoke while serving in Southwest Asia since 1990, when the Persian Gulf War began.

The NAS report notes that out of the 27 lung conditions associated with burn pit exposure—including asthma, emphysema and cancers of the throat, mouth and lungs—none met the VA criteria for proving that it was caused by service-related exposure. Mark Utell, M.D., a pulmonologist and University of Rochester Medical Center researcher who chaired the committee, noted in the report, “the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

We can’t wait 40 years. The evidence is really clear.

June Heston says the VA would have a much clearer picture if they let surviving families add death information to the burn pit registry. She refers to burn pit chemical exposure as this generation’s version of Agent Orange, an herbicide containing dioxin that was widely used to clear Vietnam jungle vegetation. An estimated 2.6 million troops were exposed to Agent Orange, according to a ProPublica report. The Agent Orange Act of 1991 gave presumptive medical coverage to some veterans who developed cancer and long term illnesses like Parkinson’s disease, or gave birth to children with defects like spina bifida, but others are still fighting for coverage.

Heston says vets struggling with toxic exposures shouldn’t have to fight the same fight, and she doesn’t want them to fight alone. “We can’t wait 40 years. The evidence is really clear,” she says.

“All doctors need to know this because they’re not going to look for cancer in a young, fit military member unless they know there’s a risk factor with burn pit exposure,” Heston says. “The biggest piece of this fight is making people aware this is what our government was doing.”