Photos by Sophie Kuller

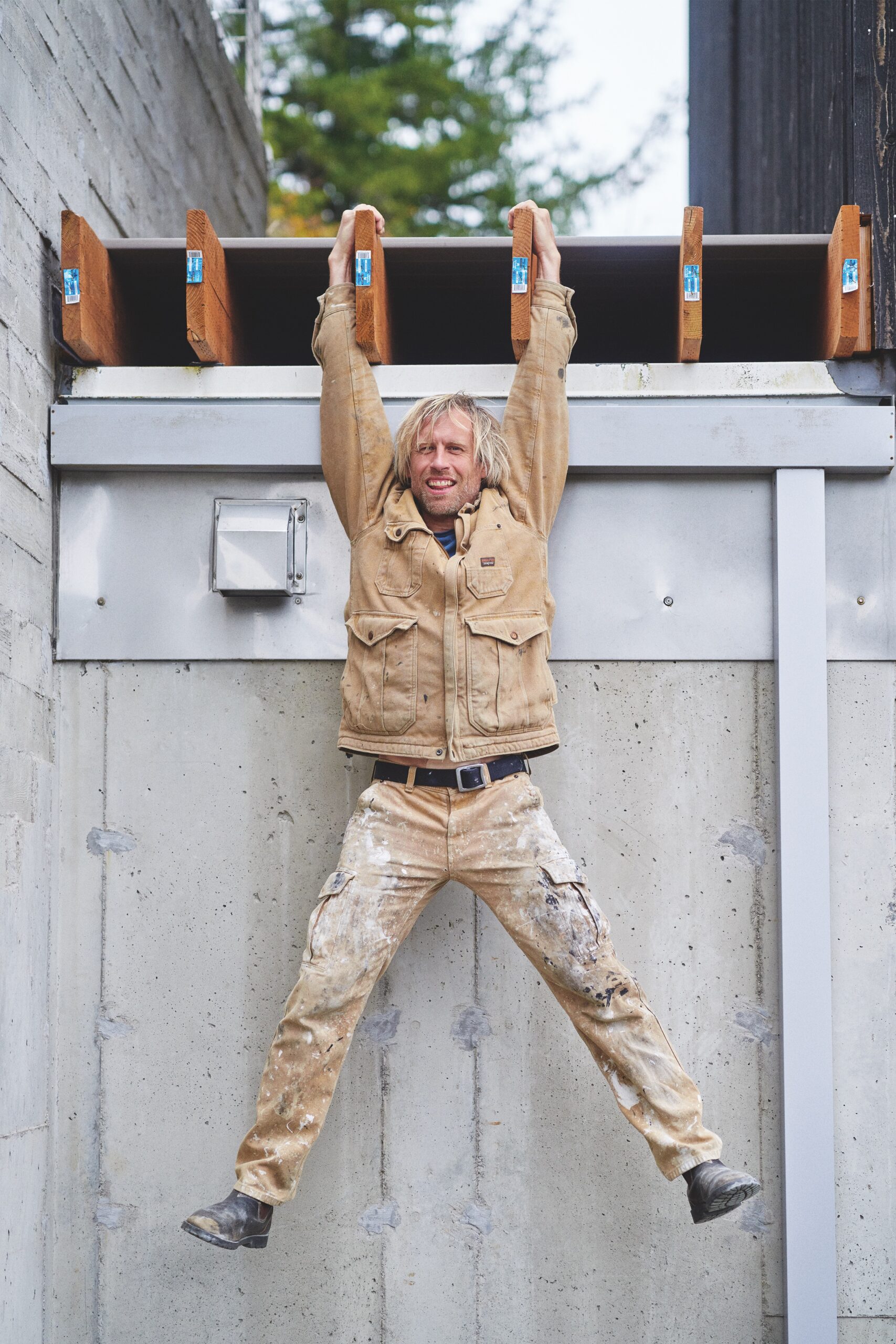

When Ben Moon answers the phone for our interview, he’s just winding down work on his house. Nestled in the sprawling picturesque terrain by Cape Kiwanda’s scenic beachfront adjacent to the Pacific Ocean, Moon’s new build is nearing completion. Soon, the longtime Oregon transplant will have a certified base on the Pacific Northwest coast, where his illustrious past nearly has a life of its own.

Here in Oregon and all before the age of 30, Moon, a renowned photographer and filmmaker, would experience a flourishing art career, a collection of some of the best crags a climber could ask for, an abundance of lifelong friends and a budding relationship with a beloved pup. He would also experience a cancer diagnosis.

Before Oregon, Moon was framing houses not for himself but for a local builder in his hometown of Grand Haven, Michigan. He was struggling to find a full-time job complementing his sports medicine background, increasingly yearning for something bigger than suburbia.

After landing a side gig at a local gear shop, Moon began consuming copious amounts of rock climbing content. Similar to how his current work online and for brands like Patagonia and National Geographic inspires a sense of wanderlust, Patagonia and Climbing magazines eventually pushed Moon to leave Michigan with a camera and a dream.

“Oregon captured my imagination,” Moon says of the expedition. “The cliffs are bigger, the rock faces are bigger, you have the ocean instead of Lake Michigan. There’s really a bit of everything in the northwest.” He lived in a Subaru station wagon and worked for a climbing company while taking photos of his and his friends’ climbs and surf sessions. Over time, Moon would eventually evolve from these humble beginnings into an impressive force of curiosity and creativity within both the adventure photography world and the cancer community alike.

When Denali came into Moon’s life, he hadn’t planned on adopting a dog. But when he was persuaded to visit a shelter one day, it was love at first sight between him and the pit bull-husky mutt. Always by Moon’s side, Denali would come to life when brought along on climbing excursions at Smith Rock State Park in the high desert of Oregon—eventually conquering the crags himself. The pair grew inseparable, their wordless bond blossoming more every day.

Denali was so in tune with Moon, in fact, that even he could sense something was off with Moon’s health.

For approximately one and a half years, Moon progressively exhibited worrisome symptoms. While living on the road in a camper van, Moon passed out one night around a campfire with friends in Joshua Tree after standing up. He brushed off his friends’ (and Denali’s) concern when he regained consciousness, attributing the incident to a recent lack of meat consumption.

Then, later that week, Moon noticed visible blood in his stool. He mentioned this to a friend, who told him it could be colon cancer and urged him to see a doctor. Like many people do, Moon immediately Googled the disease. Though he was exhibiting an alarming number of other symptoms, like gas, bloating and weight loss, he once again brushed it off as soon as he read that colon cancer diagnoses are typically given to people older than 50.

“Denial is a powerful thing,” says Moon, who was in his late 20s at the time. “I was trying to think of every reason possible that it could be something else, but I knew deep down that something was really wrong.”

Moon took a pause on van life and moved in with a friend. But even off the road, his symptoms continued to worsen. He was carrying extra pairs of underwear with him and was fearful—and too tired—to do many of his regular outdoor activities. After making a lot of excuses, he eventually decided to visit a doctor.

Denali was so in tune with Moon, in fact, that even he could sense something was off with Moon’s health.

While his nurse practitioner agreed that his symptoms could be an issue like inflammation, she made the choice to schedule him for a colonoscopy despite his young age of 29.

“That saved my life,” Moon says. “I probably would have been too advanced to even treat a month or two after that.”

Within a couple of weeks, Moon was lying on an examination table and coming out of a sedated fog after his scope to a doctor reassuring someone that women can still wear bikinis and athletes can still play sports with a colostomy bag. He then realized that the someone the doctor was talking to was him.

“I look over at my roommate and he looks like someone just gave him horrible news,” Moon recalls. “The surgeon shoved photos of the tumor in my face and was like, ‘You have cancer.’ That was the day that everything changed.”

In the early aughts, “doping,” or the use of performance-enhancing drugs, was rampant within the professional cycling community. Lance Armstrong, the formerly celebrated cancer warrior who was stripped of his seven Tour de France victory titles after a doping investigation, took the brunt of it. But many warriors, especially athletes who grew up seeing Armstrong cycle, still regard him as an important figure in the community, including Moon.

In 2004, right before he was diagnosed with colorectal cancer and long before the Armstrong controversy would explode, Moon was given a LIVESTRONG bracelet by his cyclist sister. LIVESTRONG, Armstrong’s foundation to support warriors and cancer research, was all the rage with its yellow rubber bracelets and Moon wore his for the entire time he was on a road trip. The next week, when he returned home, Moon was diagnosed.

A mutual connection was able to get a signed copy of Armstrong’s memoir for Moon right before he headed into surgery, which Moon says helped him a lot. A particular passage in the memoir still stays with him years later.

“At the very end, another cancer patient told him, ‘You don’t know it yet, but we’re the lucky ones,’” recounts Moon. “It always stuck with me. When you’ve gone through something, facing challenges and facing your own mortality, it changes you forever.”

After radiation, chemotherapy, two surgeries and eight additional rounds of chemotherapy, Moon’s life was indeed changed forever. He spent much of the summer in the hospital, Denali by his side, anchored to a bed instead of a climbing rope. It was all worth it to Moon, though.

It always stuck with me. When you’ve gone through something, facing challenges and facing your own mortality, it changes you forever.

“Yeah, I have to deal with having a colostomy bag for the rest of my life, but that’s a small price to pay for living,” he says.

A few weeks post-surgery, Moon was attempting climbs again, learning to navigate cliffs at Oregon’s Smith Rock State Park with his new colostomy bag when he had enough energy in between infusions. On days he was especially exhausted, Denali was there offering silent support, solidifying his role as “man’s best friend.”

“It was hard to have the energy for conversation and feel good, so Denali there was like having a really solid, anchoring force that didn’t need anything from me,” Moon says. “When you’re sick, everybody wants to ask, but nobody knows what to say. Conversation’s always forced and awkward. And sometimes it’s good just to be.”

After nearly a year of treatment, and a week before his 30th birthday, Moon was finally cancer-free. He continued traveling, climbing, surfing and working—all with a colostomy bag and Denali in tow.

The phrase “return the favor” took on a whole new meaning for Moon when, a few years after his own cancer battle, the vet found four cancerous lumps on Denali.

“I was like, ‘This can’t be happening. But you’ve been there for me and I’m going to be there for you,’” says Moon. He spent sleepless nights beside Denali when he was in pain, trying to offer him the same comfort Denali had given him years earlier.

The tumors were successfully removed, and Denali was cancer-free just like Moon. But about five years later, when Denali was 14 and really slowing down, Moon knew it was time to say goodbye.

By pure coincidence, a friend of Moon’s was planning to make a short film about Moon’s balancing of city life and outdoors life. Once Moon realized Denali’s days were dwindling, though, the two decided to change the focus of the film.

“Denali” quickly became a viral sensation after its release. The film, showcasing the dog’s last days in his favorite spots along the coast, is narrated from Denali’s perspective. Exploring the duality of his and Moon’s relationship in the face of illness, the piece has been viewed nearly 15 million times on Vimeo. An influx of viewer messages was received by Moon, many sharing their own cancer journeys.

“It was like [Denali’s] final gift to give back,” says Moon. “I had always joked that Denali was really good at making friends, and he continues to do that.”

The massive response encouraged Moon, typically a private person, to eventually pen a vulnerable book about his cancer journey—and Denali of course. “Denali: A Man, a Dog, and the Friendship of a Lifetime” was published in January 2020.

I had always joked that Denali was really good at making friends, and he continues to do that.

“It was extremely therapeutic,” says Moon about writing the book. “It really helped me come to peace with a lot of things and have a little bit more compassion for myself in the past.”

Moon did receive a bit of help from a new furry friend in the process. Nori, Moon’s current rescue pup who he says has the same eyes as Denali, was beside him throughout the project. Opening himself up to another dog after Denali has been one more step forward in the long-winded, non-linear path of healing from illness and loss.

“People are like, ‘Move on and get over it’ but it doesn’t work that way,” says Moon. “Cancer reminds you that you’re not in control, and you kind of have to let go. It’s like how the only way you can surf is if you dance with the wave. You can’t overthink it. It’s exhausting, but it’s also beautiful.”

Ben Moon is an adventure, lifestyle and portrait photographer and filmmaker located in Oregon. His memoir, “Denali: A Man, a Dog, and the Friendship of a Lifetime,” is available wherever books are sold. Follow Moon’s work at benmoon.com and on Instagram at @ben_moon.